Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared on Live and Invest Overseas.

In advance of the purchase of the property known as Lahardan House, the 200-year-old Georgian manor home we bought years ago to become our residence in Waterford, Ireland, we tried to have the place inspected.

This isn’t obligatory in Ireland.

The bank, to lend for the purchase of a piece of real estate, will require you to test for lead and asbestos, but they won’t call for an overall inspection of the kind we Americans take for granted when buying a house in the States.

Even though no one was telling us to arrange for a formal inspection, we wanted one and asked around for the name of an inspector.

The report from the guy we engaged was a dozen pages of general commentary related to his impressions of the place. “The living and dining rooms would benefit from re-decoration,” he noted. And: “The gardens might be cut back.”

We closed on the purchase of Lahardan House, having, it turned out, no idea what we were buying.

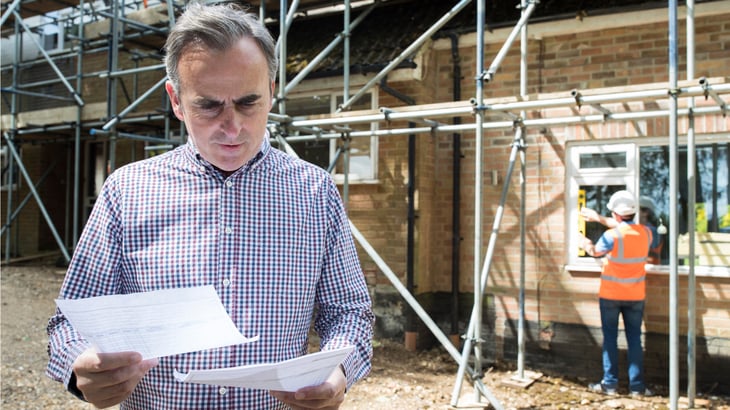

Rising Damp: What the Inspection Didn’t Reveal

Rising damp is a common phenomenon throughout the Emerald Isle. Damp from the constantly wet soil seeps into the foundation of a house and infiltrates the walls.

Left untreated, damp will rise about 6 feet before gravity halts its progress.

In our house, the damp evidently had been left untreated for a very long time. Once I understood how to recognize the signs, I could see that every wall on the ground floor was affected.

In addition to rising damp, we had rot, both wet and dry. We had mold and fungus, too, in every hidden and covered corner and crevice.

This realization turned our simple new home make-over into an all-out renovation that saw our Georgian acquisition reduced, over months, to a near-shell before the internal restoration work could begin.

It would be 18 months before the pieces of Lahardan House would be reassembled.

Lessons From Decades of Overseas Renovations

In the two-and-a-half decades since that first overseas renovation adventure in Waterford, I’ve restored a 200-year-old Spanish-colonial building in Caso Viejo, Panama, and a newer commercial building in Panama City that now serves as our Live And Invest Overseas HQ.

In addition, Lief and I have refurbished three apartments in Buenos Aires… four apartments in Paris, including the Montmartre digs whence I write today… a rental property in Medellín, Colombia… and a house and an apartment building in the States.

In all, Lief and I have renovated 13 properties in six countries.

These experiences, charming in memory but often something else at the time, are on my mind as we undertake a next project. This year we’re finally restoring the 150-year-old farmhouse we purchased a decade-and-a-half ago on a mountainside in Istria, Croatia.

As we embark on this 14th renovation, I’m reminding myself of lessons learned.

If you’re also infatuated with the idea of rehabbing the home of your dreams overseas, you might find them helpful, too.

Lesson #1: All renovation projects take twice as long and cost twice as much as you plan

We’ve not yet taken the step of allowing for this by doubling our time and expense projections from the outset.

We worry that, if we did, the inflated figures would still fall short of the ultimate actual figures by half.

Lesson #2: Everyone involved must agree on the objective from the start

Is the completed property intended for rental or for personal use? Often the answer can be both, which is when things can get messy.

Our Medellín project stands out in this regard. We renovated that apartment so personally that we were reluctant to rent it out. Fit a place out with custom parquet, hand-painted tiles, a clawfoot tub, and antique chandeliers and you become discriminating about who you feel comfortable allowing to spend the night.

We set the rental rates so high that we priced ourselves out of the market. Finally, we pulled the listing from the third agency and hired a property manager to take care of cleaning and paying the bills. It was no longer a cash-flowing asset but a straight-up expense.

You could call it a rental investment disaster story. On the other hand, the apartment is now worth five times what we paid for it. It generates no rental cash flow, but we use the property for family vacations at least once a year. I’m happy with the situation; Lief less so.

This property is perhaps our best example of what we’ve come to refer to as “The Spousal Effect.” Lief’s spreadsheeted rental projections were out the window when I took charge of the project. What short-term tourist rental renovation budget includes custom cabinetry and leather Chesterfield sofas?

Lesson #3: A renovation is one of the best ways we’ve found to engage with the local community

In Ireland, France, Panama, Colombia, Argentina, and Portugal, the places where we’ve taken on renovation projects, the architects, contractors, woodworkers, painters, and landscape designers we’ve worked with have become personal friends and have been our entree to the local scene, giving us insights into the local culture we wouldn’t have had otherwise.

Lesson #4: It’s possible to renovate a property in a country where you’re not living, but risky

Only one of our renovation projects — Lahardan House in Ireland — was undertaken in the place we called home. All the others have been managed long-distance.

The three renovations of apartments in Buenos Aires, Argentina, were handled completely by an architect contact.

We didn’t see the apartments until a year after the work had been completed because they were rented on annual leases, but the architect sent pictures on a weekly basis to update us on progress. Material selections and furniture choices were agreed via email.

The process was seamless, but I wouldn’t recommend it.

Ideally, you should plan to visit the project at least monthly during the renovation process. At critical stages, you may need to be present weekly or daily. If you’re not living where the property is located, add travel costs to your budget.